A History of Hainault Forest

By L. Peter Comber © 2017

Today the ancient woodland left in Hainault Forest is less than 200 acres in a total area of 804 acres, a mere fragment of what it had been before the middle of the 19th century. The ancient woodland was then more than 20 times as large at over 4,000 acres. The earliest records that referred to Hainault were written in the early part of the 13th century; and the first maps of Essex, drawn early in the 17th century, show Hainault Forest as established woodland. This ancient woodland would almost certainly date from the last ice age around 11,000 years ago.

About 5,000 years ago, much of Britain would have been covered in Woodland. It was the beginning of the Bronze Age in Britain that was to last for over 3,000 years. By around 2500 B.C Bronze Age people are believed to have cleared much of this woodland and established an elaborate field system for the management of livestock and agriculture in its place. Gradually, over time, much of Britain’s woodland was being removed to provide the land necessary to sustain the ever increasing population. The productivity of the land was very poor, and was believed to be less than one sixtieth of that of modern farming. It is probable that Hainault Forest woodland was fairly well defined sometime during this period, perhaps as long as 3,000 years ago.

The cultivated field systems that were in place in and around Chigwell that had survived until comparatively recently, were typically Bronze Age in their layout; Bronze Age artefacts have certainly been found in the area. The field layout terminated in a ridgeway running roughly along the line of the Manor and Lambourne Roads: probably from the River Roding through to and beyond Lambourne End; thus forming the northern boundary of Hainault forest.

The arrival of the Romans further depleted woodland in the area especially with the building of London that would also require more land for livestock and cultivation. The London to Colchester Road in all probability formed the southern boundary of the forest. It would seem that Hainault Forest woodland and its plains covered more or less the same area from that time up until 1851 when a large part was disafforested.

Hainault Forest was woodland in the South West of Essex covering an area not much larger than the 4,500 acres it was up to the middle of the 19th century. A series of ‘gates’ or ‘hatches’ probably marked the southern boundary, near to where the A12 is now. Some names still survive e.g. Marks Gate, Aldborough Hatch with West Hatch along the North- west boundary.. A hatch is a forest entrance. There are no place names ending in ‘hurst’ or ‘holt’ etc. that would have suggested that the woodland extended much beyond these ‘hatches’. Daniel Defoe in his, ‘Tour through the Eastern Counties of England, 1722’, referred to, ‘passing that part of the great forest which we now call Hainault Forest’, when he had left Ilford village and travelled along the Roman Road (A118) to the ‘Whalebone’.

Beyond to the south, there was heath and marsh land; Becontree Heath, Chadwell Heath and Little Heath etc. with marshes down to the river Thames, and. 9,000 acres of cultivated land at Barking, The gradual building of walls to contain the tidal River Thames helped to create these marshes. During the Middle Ages they were considered unfit for human habitation being ‘unhealthy and unpleasant’, and fit only for grazing sheep and cattle. Very little marshland survives today, but Rainham marsh has been purchased by the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds. The eastern boundary of the forest stretched as far as Havering, with the western boundary probably reaching the River Roding.

Hainault Forest and its woodland may well have been isolated woodland well before the arrival of the Romans. 700 years later, at the time of the Norman Conquest, it has been estimated that less than 14% of Essex was covered in actual woodland, with roughly 50% of the land cultivated, and the rest made up of grassy plains, heaths and marshland. The Doomsday survey of 1086 does not mention Hainault by name, but woodland in the area was deemed to support 2,540 hypothetical swine. Not a very large number, but the Hornbeam trees of the forest would have made poor feeding. The forest had been used as wood/pasture, i.e. timber for fuel and building and the grazing of animals since before Anglo-Saxon times, and it was continually managed this way until the middle of the 19th century, when a large part of it was disafforested; although it continued at Lambourne End until the end of the 19th century.

In 666AD, the Saxon Lord Erkenwald, founded Barking Abbey; one of the greatest houses for Benedictine Nuns. Their land eventually included not only Barking, but also what we know as Dagenham and Ilford, and a large part of Hainault Forest. William the Conqueror stayed at the Abbey in 1066AD until his Coronation in Westminster Abbey on Christmas Day 1066.

With the dissolution of the monasteries by Henry VIII in 1539 the land owned by Barking Abbey became Crown property which included 3,218 acres of Hainault Forest. Red and Fallow Deer, Wild Boar, Badger, Fox, Wild Cat and perhaps Wolves would have inhabited the area when the Norman’s first arrived. (Wolves survived in Britain until the 14th century.)

The origin of the name Hainault has been lost in time. ‘Holt’ is an Anglo-Saxon word meaning a wood, but the meaning of ‘Hain’ is unclear and could possibly be ‘high’- the land sweeps up from Fairlop plain to Chigwell Row, Lambourne End and Hoghill; some of the highest places in SW Essex. Another possibility is a monastic or community wood.The first written record was Henehaut in 1221. It has since been spelt variously as ‘Hyneholt’, ‘Henholt’, ‘Inholt’ and Henhault, etc. The present spelling ‘Hainault’ dates from around the end of the 19th century.

The word ‘forest’ comes from the Norman medieval Latin phrase forestem silvam meaning the ‘wood outside’, this refers to the land on the outside of the fenced-in estates of their Norman manors, castles and churches rtc. Today we think of the term ‘Forest’ and ‘Woodland’ to mean much the same, but in Norman times and much later, a Forest was a large area subject to special laws, and included much of Britain. Within 20 years of the conquest, a large part of Essex was declared a Royal Forest, probably by Henry 1st – ‘The Forest of Essex’. A Royal Forest was a designated area that not only included woodland, but also plains, heath-land, cultivated land, farms, villages and hamlets etc; it was an area governed by a bureaucratic administration with courts and officials etc to draft and uphold the forest laws.

The woodland at Hainault, was just a small part of ‘The Forest of Essex’, and was divided among several manors, each having land owning and communal rights. Commoners, people who owned grazing animals, were allowed to cut timber for fuel by pollarding trees but not ‘timber trees’ like Oaks; the timber from these Oak trees was required for building houses and ship building. Pollarding was only allowed between specific dates.

The interested parties were;

The Crown, as owner of the forest rights – mainly the ownership of all the deer and game in the Forest of Essex. There were Forest Courts to prosecute those who caused infringements of the Forest Laws in the Forest of Essex, which of course included Hainault.

The Owners of the Land, The largest portion of Hainault Forest belonged to the Abbey at Barking until 1539 when became under the ownership of the Crown, the Norman Barons of various manors, owning the rest. As well as the land they also owned the Timber trees.

The Commoners, tenants etc. having wood cutting and grazing rights in Hainault

Forest, that was within their manors.

Declaring most of Essex a Royal Forest gave the Sovereign ownership of all the game within the Forest of Essex, principally the deer. Deer had to have total freedom of movement; owners who were granted rights to enclose land within the Forest of Essex were required to keep their fences no more than 4½ feet in height so as to allow a doe and her fawn freedom of access.

An early writer described a Royal forest as: -

‘A territory of woody ground and fruitful pastures privileged for wild beasts and fowls of forest chase and warren, to rest and abide there, in the safe protection of the King for his delight and pleasure’.

Perhaps the earliest example of ‘conservation’, although it would not have been realised as such at the time! The ‘safe protection’ was, at first, a code of severe and stringent forest laws that provided the death penalty or maiming for poaching and killing the ‘Kings’ Deer. Maiming usually meant being blinded or having a hand cut off! The severity of these laws was so offensive that less than a century later Richard 1st (reigned 1189- 1199) and King John (reigned 1199-1216) were compelled to mitigate their harshness, the latter when he was forced to sign the Magna Carter. This also provided for a reduction in the area covered by the Forest Laws. These harsh punishments finally ceased in the 13th century under Henry III, who declared; “Henceforth let no man lose life or member for our venison”. Fines were introduced instead, and were paid to the crown and became a valuable source of revenue.

The Royal beasts of the chase were the native Red Deer, and the smaller woodland Fallow Deer believed to have been introduced earlier by the Romans. Deer-hounds were the dogs used in the hunt, a kind of greyhound that hunted by sight. Deer that were killed when hunted were gutted and the offal removed, this was called ‘umble’. The common people were allowed to collect this to supplement their diet. It is still remembered today, when someone is made to ‘eat humble pie’. Wild Boar, Roe Deer and even Hare, as well as game-birds, were also under the ‘protection’ of the King and would have been hunted on some occasions.

Since the Middle Ages, hunting had been a favourite pastime of the Crown until comparatively recent times. Hainault Forest was a particular favourite of the Crown for the hunting of deer, mainly because the Crown owned a large part of it, and because of its close proximity to London. With a Royal Palace, Bower House and Hunting Lodge at Havering atte Bower, it made it a very convenient forest for hunting.

By 1157 in the reign of Henry II (reigned 1154-1189), a large area to the east of Lambourne End and stretching as far as Havering atte Bower, had been disafforested and made into a Deer Park, so it was not subject to the forest laws. The Royal Palace has long gone, but the Bower house is still there; now a Private residence. The King’s entourage were billeted in the Bower House. Professional hunters were employed to take specified numbers of deer every year for Royal Feasts, official gifts and for other special occasions. Henry III (reigned 1216-1272) ordered an average annual cull of 4 Red deer and 40 Fallow deer from the forest with a similar number from Havering Park. In 1670, 110 Red deer and 50 Fallow deer were taken. At least two or three times this number would have probably been taken due to poaching, (in spite of the severe penalties at the time) and the Abbess at Barking Abbey and other Landowners being allowed to occasionally hunt for deer as well. There would needed to have been something approaching 800 deer in Hainault and Epping forests to sustain these sort of numbers being taken annually. Epping Forest was used mainly as a reserve for deer to migrate to or be driven into Hainault Forest, and to ‘top up’ Havering Park occasionally.

The last deer believed to have been hunted was a hart, a 5-year-old red stag, run from Hog Hill to Plaistow in 1826!

Hainault Forest was non-compartmentalised, i.e. it was not divided up into areas that would be pollarded on a rotational basis. Coppiced woodland was compartmental and had to be fenced off to keep grazing animals out thus preventing the new shoots from being browsed; the coppiced timber that was cut was required for different purposes to that cut, from pollard trees!

The Landowners, including the Crown, owned the timber trees as well as the land. ‘Timber’ trees, mainly oak, were used for building; (practically all medieval buildings were oak timber framed,) and for use by the Navy. Oaks were taken regularly, although Hainault would not have been a good source for this timber, the oaks were not of good quality. The Royal Navy increasingly required oak for shipbuilding; but the oaks from Hainault were used primarily for repairs. In 1794 some 340 Oak trees in Hainault Forest were felled for naval use. The first decade of the 19th century yielded an average of 114 tons of oak per annum. Both the New Forest and the Forest of Dean each yielded considerably more, in fact almost ten times as much oak during the same period.

The Commoners, owners of animals and land etc. (not Peasants) had wood cutting rights - the right of ‘Lopwood’ - to lop the trees for use as winter fuel and also to graze their animals. Certain houses were allocated a load of wood each year (about a ton.) This had to be done in such a way that the trees were neither destroyed nor unnecessarily injured, and at such a height so as not to destroy the covert or browsing for the deer and the domestic animals. Trees were lopped about 8ft from the ground using a long handled axe, thus ensuring the deer and other grazing animals could not reach the new growth that sprouted from the cut surfaces. Spray and trimmings from the cut boughs were left on the ground as food for the deer and grazing animals. Faggots, no doubt would be collected for use by Bakers to heat their ovens. Once maiden trees were lopped, they became ‘pollards’, each tree was pollarded on a 15 to 20 year cycle; when the re-growth had reached the ‘thickness of a mans wrist’, and was only allowed between specific dates. In Waltham (Epping) Forest this was from midnight on All Saints Day (11th November) until Lady Day (25th March); if anyone had not started cutting by midnight on the 11th then their right to lop wood lapsed. It would have operated in a similar way in Hainault; it was illegal at all other times. It was also illegal to cut the ‘King’s Vert’-- small trees and under-wood, thereby depriving the deer of food and cover; it included small trees such as, Crab, Pear, Thorn and Holly. The vast majority of the pollarded trees were Hornbeam, with some Ash and occasionally Oak.

Trees that are pollarded do not put on much growth but become ‘vase’ shaped, called a bolling, thus making the tree appear much younger than its true age. The life of the tree is lengthened considerably by regular pollarding, with many trees being centuries old. Maiden or spear oaks had to be left to grow into timber trees, and were marked by the forester with a ‘broad-arrow’. Topping maiden oak trees to make pollards was a constant source of friction between the Commoners and the Landowners, as once lopped, the trees could not be sold for timber. Trees in Hainault were last pollarded at the end of the 19th century at Lambourne End, the last remaining piece of ancient woodland to be used in this traditional way. When pollarding is stopped the trees eventually become top heavy and are very vulnerable to decay and high winds in bad weather; in recent years a considerable number have lost limbs that have broken away splitting the trunk or having become top heavy with very large limbs, they would topple, complete with their shallow root plates.

The woodland in Hainault Forest was a mix of pollarded and timber trees, with open areas, heaths and grassland, called ‘plains’. Some areas are still known by the names that were given to these plains such as Cabin, Weddrell’s and Taylor’s plains at Lambourne. But they have now become secondary woodland since the grazing of animals was stopped more than a century ago. Fairlop plain, near Barkingside, is now a sports and leisure centre - Fairlop Waters. It was a fighter airfield during the Second World War.

Grazing rights or pasturage for domestic animals was also granted to certain Commoners; prior to the Reformation, Barking Abbey had the rights to pasture sheep in Hainault. (In 1630 the Forest Court held that sheep were not commonable because Deer, allegedly, will not go where sheep are grazed!). Cattle were the main animals pastured; with rights of pannage for pigs. Pannage was allowed when the green acorns first dropped, between September 14th and November 8th. Green acorns are toxic to all the other grazing animals including the deer. The pigs had to have rings put through their noses to stop them from ‘rooting’ too deeply and damaging the forest floor. All animals being pastured had to be branded with a parish mark. It was illegal to graze goats and geese in the forest, because of the damage they would do to the grazing. Cattle were excluded from the forest during the ‘Fence- month’; fifteen days before and fifteen days after old midsummer’s day, the time when the deer ‘drop’ their fawns.

Fines, which went to the King, were imposed by the Forest Courts on those breaking the forest laws, such as grazing their animals in the forest without pasture rights, grazing too many livestock, grazing geese and goats or grazing at the wrong time of year etc. etc. Deer and domestic animals achieved some sort of balance in the forest, providing just enough grazing to maintain the plains and heaths within the forest.

Charcoal making or ‘charcoaling’ as it was called, was carried on in the 14th century and probably earlier; it continued until the 19th century. Charcoal was an essential ingredient of gunpowder as well as being used as fuel where great heat was required by the likes of blacksmiths and for iron smelting. The men who made charcoal were called Colliers and called their product ‘coal’. Collier Row dates from 1479 and gets its name from a row of cottages where these Colliers lived in Collier Row Road. Other place names are associated with the forest, such as Chigwell Row, a row of cottages on the Chigwell side of the forest and Fairlop from a very large and famous oak tree – the Fairlop Oak. Barkingside simply meant the Barking side of the Forest. In 1539 when it came under the ownership of the Crown, Ilford was still a small village within the parish of Barking. With the coming of the railway, Ilford expanded rapidly and became a parish in its own right in 1888. Whalebone Lane gets its name from the rib-bone of a whale, erected as a monument to a 28ft long great whale taken from the River Thames in 1658, (the year Oliver Cromwell died.) It was situated along the Roman Road just to the east of the ‘Lane’; at the edge of the ‘Forest of Essex’, close to the Havering Stone. (See below in 1641.)

At various times the Crown has used the Forest of Essex to raise extra revenue. In 1224, Henry III (reigned 1216-1272) granted a Charter of the Forest in consideration of one-fifteenth of all the movables of the Kingdom. The Charter was a perambulation of The Forest of Essex reducing it to about 60,000 acres in the south west of the County. After he obtained the money, Henry did not keep to his word, and kept the boundaries as they were for the rest of the century!

Edward I (reigned 1272-1307) in 1300 demanded one-tenth of a penny from all his subjects, Parliament granted him a fifteenth on the condition that a new perambulation of the Forest of Essex be made. In 1301 it was reduced to 60,000 acres much the same as it should have been some 77 years earlier! This perambulation remained in place for several centuries, although it was subject to numerous disputes as to its exact limits.

At the dissolution of the monasteries during Henry VIII’s reign, the Crown took over the lands and that portion of Hainault Forest vested in the Abbey at Barking, thereby owning a considerable part of the forest; some 3,218 acres became crown land!

Charles I (reigned 1625-1649) attempted to rule without Parliament. In 1634 he needed to raise money, so he had the boundaries of The Forest of Essex extended back to where they had been over 300 years earlier! The occupiers of land within the enlarged boundaries were proceeded against for “illegally encroaching on the forest”. He was successful in every case, and in a few years, was alleged to have raised some £300,000. This ‘Forest’ enlargement was one of several national grievances, and in 1640 the Long Parliament passed an Act limiting the forest to its pre-1634 area. In the following year, 1641, a perambulation was made agreeing substantially with that of 1301. The River Lee was made the Western boundary, with the Roman Road, (London to Colchester) the Southern boundary. The Northern boundary was a series of ditches and banks stretching from Roydon via the River Roding, to Curtis Mill Green; with a line of eight ‘stones’, forming the Eastern boundary.

The first most northerly, ‘Richard’s’ stone, was at Curtis Mill Green, followed by the ‘Navestock’ stone. The boundary then followed the Bourne brook and around Havering Park to the ‘Park Corner’ and ‘Collier Row’ stones. Stones 5, 6 & 7; the ‘Warren’, ‘Mark’s’ and ‘Forest Bounds’ stones respectively were along the eastern side of what is now Whalebone Lane. The most southerly, the ‘Havering’ stone, is about 400yds to the east of Whalebone Lane along the Roman Road. The stones were restored in 1909 by the Essex Field Club and are still in place, although the ‘Collier Row stone’ could not be found and was replaced. A plaque on each stone commemorates the event. (The ‘Warren’ stone was removed along with rubble by road workers several years ago and has never been found!)

Hainault Forest was in grave danger of being destroyed in 1642 after the Civil war. Oliver Cromwell tried to dispose of the unenclosed parts of Hainault Forest for the benefit of the ‘Commonwealth’, but, fortunately it proved to be too difficult with all the different interests to be satisfied. The Forest laws and courts were not enforced at this time.

The Forest courts were renewed after the Restoration of the Monarchy in 1660. Charles II (reigned 1660-1685) occasionally hunted in Hainault Forest, and was the last monarch to hunt there. It was during Charles’ reign, that the Royal hunting excursions into the forest were discontinued and gradually the Forest laws fell into desuetude. The principal forest courts never met after 1670, and the only surviving court, the Court of Attachments, had limited powers. Various Acts of Parliament were passed to prevent enclosures and deer stealing, but they were largely ineffective.

In 1817, the Commissioners of Woods and Forests applied to Parliament for an act to disafforest the whole Forest. The Bill passed the House of Commons but was withdrawn through lack of time in the House of Lords.

Deer stealing continued unabated, with many of the local inhabitants owning Greyhounds or Lurchers, dogs traditionally used by Poachers and Gypsies for hunting. Abuse of the Forest continued; as well as the stealing of deer; timber and topsoil; sand and gravel was also being taken illegally. In 1830 the Court of Attachments reported 73 illegal enclosures, but no action was taken to abate them. With the Forest largely ungoverned and unprotected, the government of the day considered the 4,300 acre Hainault forest to be ‘waste’ and could be better used as farmland; with this recommendation, and in spite of many objections an act was passed in 1851 abolishing the deer and allowing the portion owned by the Crown, some 1,917 acres, to be enclosed with about 100,000 trees, for disafforestation.

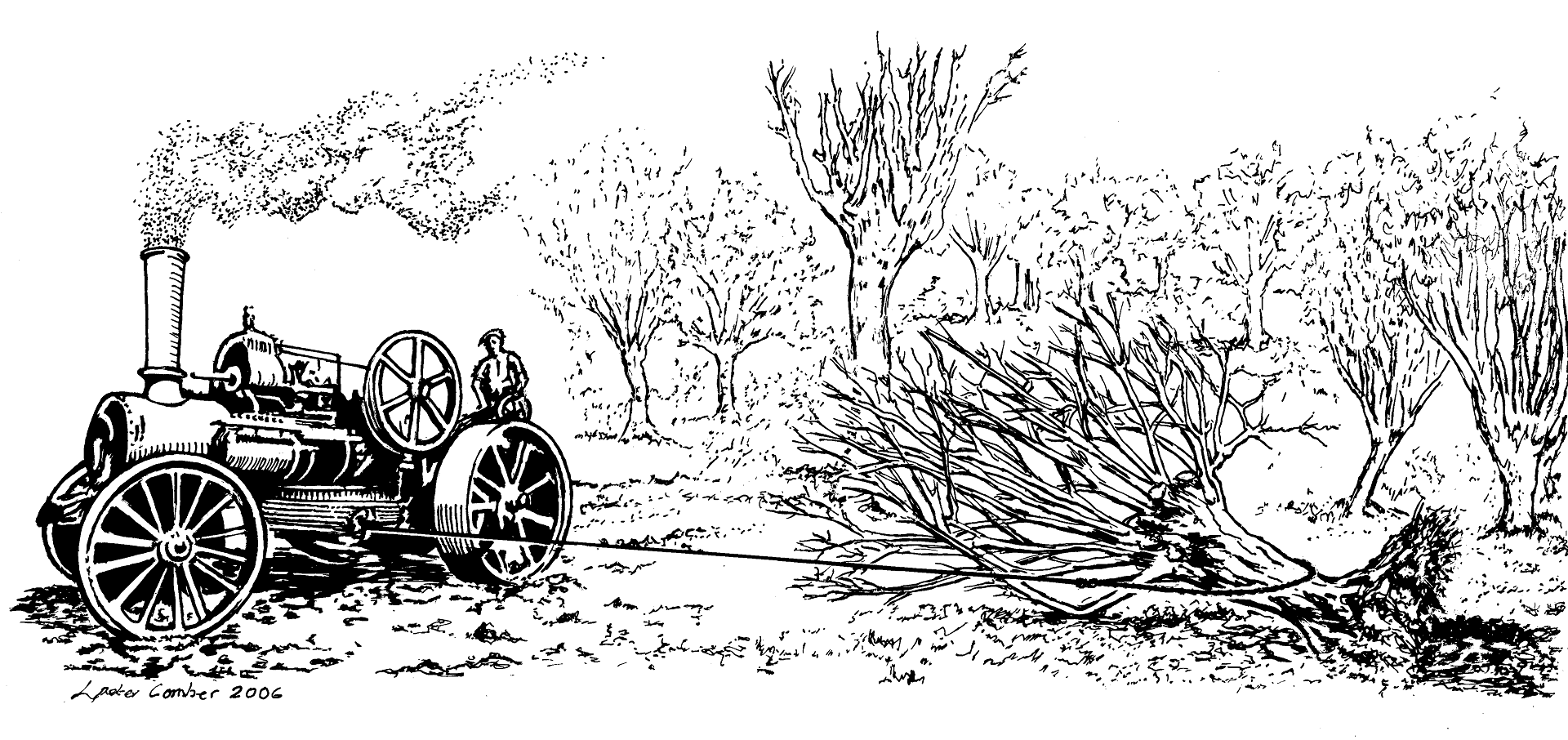

The Government entered into a contract for using steam ploughs*, and in the space of just six weeks, working day and night, a large area of Hainault Forest was grubbed out by the roots. The Oak trees were stripped of their bark for tanning, a valuable product used in leather making. (Tanners Lane is nearby at Barkingside!) Seeing so many trees lying on the ground stripped of their bark must have been a sorry sight! It would be some time before all the timber was removed, probably via Aldborough Road, to the docks at Barking to be sold;

A steam plough engine being used to grub out a Hornbeam pollard.

* Steam ploughs were steam engines fitted with a horizontal pulley wheel underneath that were used for ploughing. They operated in pairs, one on each side of a field, pulling a 7 furrow plough back and forth across the field, working their way along the field. At the time ploughing by this method was in its early stages of development.

The area cleared was laid out as farmland at a cost of £41,800, which was defrayed out of the money realised by the sale of the bark and timber. Three Farms were built, complete with farm buildings and farm labourer’s cottages; Forest Farm in Forest Road, Hainault Farm in Hainault Road and Foxburrows Farm off the Romford Road near Hog Hill. All the farm buildings have date plaques on them, either 1855 or 1856. The plaques had the letters VR and PA cut in to them with a raised lead metal crown in the centre. Some of the crowns have been stolen for their lead! (VR, Victoria Regina; PA, Prince Albert.)

Further Acts in 1858 and 1863 allowed the remainder of the Forest to be shared out among private owners, many of whom were slower than the Queen in converting their shares to farmland, as by then the next farming recession had set in. About a quarter of the original Forest was still intact in 1872. Many fragments remained until well into the 20th century. These fragments had all gone by the end of the century. A section of 188 acres at Lambourne End was spared and allotted to the Parish in 1861 for use in the traditional way, i.e. grazing and pollarding, this continued until the end of the 19th century.

In 1866, George Shillibeer, a coach maker, obtained, in perpetuity, 49.9 acres of land in Hainault Forest at Chigwell Row for the inhabitants of Lambourne and Chigwell Row to use as a Recreation Ground. About half of the area is a recreation ground and the rest to the south is ancient woodland; a remnant of Hainault Forest, with many pollarded Hornbeams and mature Oaks. It is separated from today’s Hainault Forest by Romford Road, a dual carriageway.

George Shillibeer 1797-1866 was a coach maker in Bloomsbury who built the first two omnibuses in England. He introduced the omnibus on July 4th1829, carrying passengers in London,. He lived at ‘The Grove’, an Elizabethan Manor House in Chigwell Row. It was being used as a club when it caught fire in 1962 and was considered to be too badly damaged to be restored.

Hainault Forest had always supported a large population of Gypsy’s and Tramps; disafforestation forced many of them to live on the outskirts of the area in places like Collier Row and Marks Gate. They made money by making and selling pegs etc. and by horse-trading in Romford Market. (In about 1935 I can remember my mother buying pegs from a Gypsy woman calling at the house selling pegs!) Over 300 gypsies that had encamped on the common at Chigwell Row were causing a lot of damage to the Forest and intimidating the local population with their stealing and bad behaviour. Cyril Groves said his father told him how the local children were often ‘relieved’ of their lunches on their way to the school opposite the Common by the Gypsy children; and how the gypsy women would settle their arguments by stripping to the waist and fighting in the yard of the Two Brewers public house!

The destruction of Hainault Forest in such a short time of only six weeks, caused public shock and outrage, it was indeed a public scandal! Efforts were made to avert the same fate for Epping Forest and were largely successful, but nothing was done to try and save what remained of Hainault Forest. The many fragments remaining were gradually lost, one after the other, to farmland and housing. A large part of the 100 acres of Ancient Woodland at West Hatch went in the 1920’s for housing. Some large oak and pollarded hornbeam trees remain in the area, and can be seen in gardens and alongside the roads in Manor Road, Forest Lane and Stradbroke Drive, Chigwell.

After a long and hard fought successful battle in helping to save Epping Forest, Edward North Buxton (1840-1924) of Knighton, Buckhurst Hill, turned his attention to what remained of Hainault Forest. With the support of the Essex Field Club, who regularly held meetings around the forest area, a meeting was called on Saturday 14th June 1902 for all interested parties to support the reafforestation of Hainault Forest. It included representatives from Essex County Council, West Ham, Barking, Ilford, Woodford, Buckhurst Hill, Leytonstone, Wanstead, Leyton, Walthamstow and Chingford Councils, The Commons Preservation Society, The Press, and Field Club members and other interested parties. (Edward North Buxton was chairman of the House of Commons Preservation Society and a Verderer of Epping Forest.)

The Times Newspaper on the 17th June reported the meeting where Mr. E. N. Buxton, led the group for three hours. They "tramped the turf, jumped the watercourses, waded through the ponds, squelched through mud, and scrambled through the bushes, not without damage, but with unflagging interest and good humour."

Tea was taken in a large tent, following which details of the scheme were given by Mr Buxton, with complimentary speeches by Prof. Meldola, President of The Essex Field Club, Mr Shaw Lefevre of The Commons Preservation Society, and other gentlemen. “A curious and slightly sinister background was formed by a ring of gipsies, who have a very particular interest in the matter and who drew near to listen to their fate."

With this support, Edward North Buxton took the opportunity to repurchase some of the enclosed land that also included Fox Burrows Farm. (The land around the farm was rather poor and it had not been very successful as a working farm.) After general agreement, Mr Buxton privately negotiated with the owners of adjacent land in Lambourne and Chigwell Row, namely, Captain R.W. Ethelston and Lieutenant-Colonel A.R.M. Lockwood, both retired, to purchase their portions. Farming was in the doldrums at the time so they were willing to sell. The 475 acres at Fox Borrows Farm owned by the Crown, some common land and the 188 acres at Lambourne End were also to be included; making a total of 804 acres to be purchased as a Public open space.

The total cost of the purchase was £21,830, of which one half had already been promised. Essex County Council, the Corporation of West Ham, and the District Councils of Leyton, Wanstead and Ilford all contributed and £2,500 was privately subscribed. Even the Great Eastern Railway Company contributed £500, thus making a total of £12,000.

Mr Buxton approached The Corporation of London for the remaining £10,000, but the request was turned down. (They had paid nearly £250,000 for Epping Forest some 40 years earlier). The London County Council’s Parks and Open Spaces Committee were approached in May 1902. They carefully considered the scheme, and after viewing the site and satisfying themselves that the asking price was reasonable, they recommended the London County Council contribute the £10,000 asked for, and also to assume the management of the land when it was acquired. It was estimated the cost of maintenance would not exceed £300 a year! The recommendations were adopted on 20th January 1903 and the necessary statutory powers were obtained in the ‘Hainault (Lambourne, Fox- Burrows and Grange Hill) Act 1903’. In addition to the area acquired under the Act, a further 2 acres of land opposite the Beehive Inn (now the Camelot - Miller and Carter.) was purchased in 1904 by Mr Buxton and transferred to the London County Council.

The purchase of the 80 acre Grangehill Forest adjacent to Claybury Asylum, fell through due to the vendors insistence that the asylum patients be denied access to the woods. This area is now owned by the London Borough of Redbridge and is a public open space. Prior to 1851 it had been part of the Western side of Hainault Forest.

The Animal Pound at Lambourne End, dated 1904. The gate just seen on the left was stolen several years ago.

In Lambourne End the lopping of trees for winter fuel and the Pasturage (grazing of domestic animals) had come to an end by 1903 after many centuries of traditional use by the local people with grazing and lopping rites. (By the turn of the century there would have not been many using the woodland in this way!) The ‘locals’ who ignored the ban on grazing, had their animals placed in a specially built pound . (It is in the car park opposite the public house.) Owners of impounded animals had to pay a fine for each animal to get them released.

Hornbeam trees in Hainault Forest in about 1950, 50 years after they were last pollarded. 60 years further on they have become top heavy and a great many have fallen in the winter gales. (Repollarding trees at this late stage inevitably results in the death of the tree!)

Gypsy’s

In 1903 it was said that as many as 300 Gypsy’s were camped on the common at Chigwell Row and Lambourne End, having been driven there by the various 19th century acts allowing the forest to be cleared. 300 may have been a slight exaggeration but there was a large number of Gypsies occupying all of the common and the adjacent woodland. Removing them was going to prove very difficult. Mr Buxton paid them handsomely, some 30 shillings each to move, which they did, but they returned a couple of days later and then refused to leave! Mr Buxton was in no mood for compromise and brought a team of burly men and carthorses from the family brewery, Truman, Hanbury & Buxton, and together with Rangers from Epping Forest, tried to physically eject them. As fast as they pulled them off they came back, tying branches to their wheels to prevent them from being moved. One was alleged to have tied his wife to the wheels but all to no avail. Several Gypsy men were arrested and gaoled on condition that they would not be released until they moved off the land. After three days when most had been ejected the rest finally moved off.

Keeper Butt of Epping Forest was one of the keepers who had been brought in to assist the Brewery workers in removing the gypsies; his first hand account of the removal operation is contained in ‘A keepers Tale’, by Fred J. Speakman'.

The land that had been purchased from the Crown and other owner’s, totalled 804 acres, of which 253 acres was woodland with 551 acres of arable land on Fox Burrows Farm and some adjoining fields.

The work of re-afforestation was carried out on the farm and fields under the direction of Edward North Buxton at an estimated cost of £2,800. The arable land was sown with suitable grasses, heath land areas planted with gorse and broom, and other areas with a variety of forest trees. Six acres (Dog Kennel Wood) opposite Hainault Lodge at Hog Hill were planted with 1,750 trees of various kinds including Beech, a species that was previously unknown in Hainault Forest. The land is too acidic for Beech and today many of these trees have not survived, and few of those that are remaining are not in a healthy state. The Foxburrows Farm and buildings that were built in 1856 were retained and adapted for various purposes, the 8 cottages for the staff. The Farm House was pulled down in 1973.

An 18 hole Public Golf Course was put in place around the Southern & Eastern sides of the Farmland and Forest.

The Dedication of Hainault Forest took place on Cabin Hill on the 21st July 1906 by the Right Hon. the Earl Carrington, G.C.M.G., President of the Board of Agriculture and Fisheries. The Chairman of the London County Council, the Parks and Open Spaces Committee, Edward North Buxton and other dignitaries with their wives in their finery attended. Local children at Chigwell Row were given Union Flags to wave as the carriages went through, probably entering the forest at Lambourne End, opposite Hoe Lane; a wide path there goes straight to Cabin Hill. Another entrance in Romford Road also had a wide path that led to Cabin Hill. With the L.C.C Band in attendance, it was a very grand occasion.

Earl Carrington paid tribute to Edward North Buxton,

“…..to whom it was largely due that a fine open space had been rescued and saved for the use of their fellow citizens. In the name of the public of our mighty country, in their name, and in the name of their children and their children’s children, I declare this magnificent forest of Hainault open and belonging to the public for ever and ever.” Earl Carrington proclaimed. This pronouncement was received with loud cheers from the thousands of those present, as the London County Council band played The National Anthem.

The Lake and Two World Wars

Shortly after the dedication, work was started on digging a lake adjacent to Hog Hill pond or Lord’s pond a 100 yards or so from the Romford Road, probably around 1907. 100 unemployed men from London were brought in to Fairlop station on the recently opened North Eastern Railway’s line between Ilford and Woodford. (From Liverpool Street Station) Cyril Groves said his father, Jimmy, had said that they were marched to the site; each one was given a 1/- (5p) a day and a mug of tea; they were provided with shovels; but not wheelbarrows - so as to make the job last longer!

It was to have been dug to be used as a boating lake with an island in the centre. It had just been completed when the Great War had started and the boating idea was shelved. By the end of the war in 1918 the LCC had gone off the idea altogether and it was never used for boating.* Two posts about 20 ft apart were situated in the middle of the lake to the west of the island, most likely to attach the boats to at the end of the day. The posts remained in place for many years probably going in 1976 when dredging took place. A local man Mr Joseph Frederick Faux (1867-1941), (pronounced Fawkes), said that during the Great War, a target was stretched between the two posts for use as gunnery practice by WW1 aircraft based at the landing ground at Hainault Farm! He also remembered that some German prisoners of War were camped in the barns at Foxburrows Farm and worked the land on the farm.

* In the last few years there has been boating on the lake in the summer months.

German prisoners of War, working on the land at Foxburrows farm during WW1.

Early on in the Great War, less than a mile away on Hainault Farm, 60 acres were requisitioned from a Mr W. Poulter for use as an Aircraft Landing Ground for aircraft to attack the German Zeppelin airships that were bombing London and causing panic. By October 1915, it was completed and Landing Ground III at Hainault Farm came into service; initially it had two SE5 aircraft, but by mid 1916, six aircraft were operating from there with some degree of success. Aircraft were towed up to the top of a hill, close to Hog Hill, to assist them when taking off; the hill and the farm and buildings are still there. Hainault was the first airfield to be equipped with Sopwith Camel aircraft in 1917!

German Gotha bombers replaced the Zeppelin airships and started night raids on London causing further panic and alarm in the Capital. The Sopwith Camels were hastily re-equipped with cockpit lighting for night flying to counter these raids. The pilots were billeted in the farmhouse. A bell on the outside of the farmhouse was rung to summon the pilots in an emergency. Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur ‘Bomber’ Harris of the Second World War started his flying career there in 1918, commanding the night fighter squadron. On the edge of the Landing strip, close to the road and almost opposite the farmhouse in Hainault Road, engineering workshops were built to service the aircraft etc. The buildings are still there, they became Smiths Tarpaulin factory some time after 1919 when the Landing ground was closed and the grass landing strip returned to farmland. Since the mid 20th century they have housed several small industrial units. The WW1 camouflage painted on the buildings could still be seen over 50 years later, but it has now weathered and is no longer visible.

Between the two World Wars, civilian aircraft flew from Fairlop plain - from both sides of Forest Road. A proposal in 1938 to use Fairlop Plain as a Civil Airport to serve London was shelved at the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939.

At the end of 1940, just over a year after the commencement of the Second World War on 26th September 1940, Fairlop Plain was taken over by the Air Ministry for use as a Royal Air Force fighter airfield. In just under one year on 1st September 1941, it became fully operational, with three runways and ancillary buildings, becoming a satellite to Hornchurch a couple of months later. Early on, a Czech Squadron No.313 operated from there. Squadrons of Spitfires, Hurricanes, Mustangs and Typhoons all flew from there at various times. By March 1944 it was no longer required as a fighter airfield and became No. 24 Balloon centre – part of the massive balloon barrage surrounding London to bring down any low flying enemy aircraft and the pilotless V1 flying bombs or ‘Doodlebugs’ as they were commonly called. The centre was operated by the WAAF. (Women’s Auxiliary Air Force) and was credited with bringing down 19 V1s. The station finally closed in August 1946.

The Fairlop Oak

The Fairlop was a name given to a very large oak tree, Quercus roba, that was situated about one mile east of Barkingside, and just South of Forest Road. It was reputed to be 900 years old, and measured some 36ft around its trunk at 3ft from the ground. One of its limbs was said to measure 12ft round! The branches of this very large tree were said to be 300ft across, and to shadow over an acre, hence its name of Fair-lop. Undoubtedly this was a very large tree, but this maybe somewhat of an exaggeration! The name Fairlop allegedly comes from a visit by Queen Anne (1702-1714) and is recorded in one of the verses from a song called “Come, come my boys.”

To Hainault Forest Queen Anne did ride,

And saw the old oak standing by her side,

And as she looked at it from bottom to top,

She said to her Court, it should be a Fairlop.

The tree was a gathering place for many; with Archers, Picnickers, Gypsy’s and the famous Fairlop Fair all meeting there, damage to the tree was inevitable, not least by the compaction of the soil around it. By the eighteenth century the old tree was in decline, attempts were made to arrest its decay; it had become hollow and was shored up. A palling was erected around it with a notice saying, All good foresters are requested not to hurt this old tree a plaster lately having been applied to its wounds.

The ‘plaster’ was invented by William Forsyth in 1789; George III’s gardener at Kensington Royal Gardens. He published his findings; ‘General observations on the Diseases, Defects and Injuries of all kinds to Fruit and Forest trees’, and claimed it never failed to cure the ailments of trees whatever their nature!

Take one bushel of fresh cow dung; half a bushel of lime from old buildings (Ceilings of rooms preferably); half a bushel of wood ashes and a sixteenth of a bushel of river sand. Sift the dry articles fine before mixing all the ingredients; work together with a spade then a wooden beater until the stuff is very smooth. Then prepare the tree properly by cutting away all the dead, decayed and injured parts till you get back to healthy wood, rounding off the edges with a draw knife. Then lay the mixture on one eighth of an inch thick. Take a quantity of dry powder of wood ashes, mixed with a sixth part of the same quantity of burnt bones, put it into a box with holes in the top, and shake the powder onto the surface of the mixture, leave for half an hour to absorb the moisture. Apply more powder rubbing it gently with the hand, repeating the process until the surface becomes dry and smooth.

It is extremely unlikely that this would have worked, but we shall never know, as not many years later on 25th June 1805, a large picnic party kindled a fire near the tree; after they left, it spread, burning the main branch and part of the trunk. High winds in February 1820 completed the old tree’s destruction.

A builder named Seabrooke bought the timber. Many objects including souvenirs were made from the wood; the Pulpit and the Reading Desk at St Pancras Church and the Pulpit at Wanstead Parish Church were also made from the Fairlop oak timber.

The Fairlop Fair

The fair was started by accident in about 1720 and took place under the Fairlop Oak. Daniel Day, a Pump-and-Block-maker from Wapping was the son of a Brewer and was born in Southwark in 1683 in the Parish of St. Mary Overy. Accompanied by his friends, he used to come to Fairlop on the first Friday in July to collect rent on the property he owned in the area. Afterwards, he and his friends used to withdraw to the Fairlop Oak to feast on and distribute beans and bacon from sacks they had brought with them; passers by would be invited to join them. As the years went by, more and more people joined the party, and by 1725 it had become a public fair with sideshows and entertainments.

Day travelled down from Wapping in a boat carved from a single trunk of a large Pine, with wheels and mock sails, and drawn by six Shire horses. 30 or 40 of his pump-and-block-maker friends travelled with him accompanied by a band of musicians.

A poet who travelled with Day wrote: -

O’er land our vessel bent its course,

Guarded by troops of foot and horse;

Our anchors they were all a-peak,

Our Crew were baling from each leak,

On Stratford Bridge it made me quiver,

Lest they should spill us in the river.

The founder of Fairlop Fair was remarkable for his benevolence; it was said that he relieved the poor at his gate every day and would often lend sums of money to deserving persons, apparently charging no interest for it. He was never married, but treated his sister’s children as if they were his own.

A female servant, a widow, had been with him for 28 years. In life she loved two things, her wedding ring and her tea, when she died he buried her with her ring on her finger and a packet of tea in each hand! This was all the more remarkable, as he ‘disliked the stuff and never made use of it’.

As Day was approaching old age, the Fairlop Oak lost one of its branches, seeing this as an omen of his own approaching end he had the limb made into a coffin for himself. He took care to try it lest it should be too short! He died on 19th October 1767 aged 84, and at his own request, his body was borne in its coffin by boat down the River Thames to be buried at St. Margaret’s Parish Church at Barking. Day had a prejudice against road travel, especially horses, as he had been thrown from one of them on his many journeys and crippled.

Day’s idea of travelling in a ‘Boat’ was copied, as there were soon several similar boats travelling from London’s East End to the Fair at the Fairlop Oak.

After Day’s death, the Fair continued and went from strength to strength, stretching over three days, with the third day, ‘Fairlop Sunday’ becoming the more popular. By 1736 gambling and the selling of liquor was taking place. In 1803, a missionary counted 108 places where drink could be bought and 72 gaming tables were operating!

An estimated 100,000 people were attending the fair travelling from miles around, it had become a place ‘where a great number of people met in a riotous and tumultuous manner, selling ale and spirituous liquors, keeping tippling booths and gaming tables to the great encouragement of vice and immorality’.

The fair was also a meeting place for Gypsies; they travelled from far and wide for their annual reunion. After disafforestation in 1851, the gypsies held their reunion on land near The Bald Faced Hind public house. The building was replaced in about 1930 by the The Bald Hind public house, itself taken down in 2007/8. A block of luxury flats has been built on the site..

The authorities had tried several times, unsuccessfully, to close the fair, as it had become a drunken orgy for thousands of people who were causing much damage to the forest. It continued long after the old oak had gone, and it wasn’t until the land was cleared and enclosed in 1851, that it finally came to an end. Attempts were made for it to be continued at the Olde Maypole Inn but it never really succeeded there. The Olde Maypole Inn at that time was a public house situated near the junction of Tomswood Hill and Fencepiece Road - it has long gone.

Inhabitants of the Woods

From age to age no tumult did arouse

The peaceful dwellers; there they lived and died’

Passing a dreamy life, diversified

By nought of novelty, save now and then

A horn, resounding through the neighbouring glen,

Woke as from a trance, and led them out

To catch a brief glimpse of the hunts wild rout

The music of the hounds; the tramp and rush

Of steeds and men; and then a sudden hush

Left round the eager listeners; the deep mood

Of awful, dead, and twilight solitude,

Fallen again upon that forest vast.

Dido

As well as the gypsy’s there were still a few tramps and vagabonds living in what was left of Hainault Forest. The most famous of these was ‘Dido’, where locally he was well known as a herbalist. He came to Chigwell Row in 1880, and set up camp in Hainault Forest by the side of Sheep Water well just inside the woodland opposite Chigwell Row School.

Around the turn of the century Alice Clark (1890-1964) was attending Chigwell Row School. She used to visit him with other local children when school had finished for the day. She said his camp was under a large oak tree to the left of Sheep Water, and that he always wore a type of ‘Fez’ with a tassel on the top. (It was probably a Victorian Smoking Cap!) She said they used to call him ‘Dido Jones’; this may have been the local children’s nickname for Dido, as there are no other known references to the ‘Jones’ bit. He always referred to himself as Dr Bell, as he claimed many cures for his Herbal medicines. He wasn’t a gypsy although he lived like a gypsy. His reputation as a herbalist spread in the Chigwell and Lambourne communities, and he was always in demand. Many of his remedies included ‘cures’ for whooping cough, measles, burns and liver complaints. He believed that “the liver is the kitchen of the body, and if the kitchen is not in order then the whole house will be upset”. The sick would be visited, even those with contagious diseases such as diphtheria and scarlet fever, when others would stay away. Rare ferns collected from Loughton, were made into a ‘green ointment’ that he used for cuts and bruises, sprains, rheumatism and chilblains.

The story goes that one winter’s day; the driver of the horse drawn bus that went from Lambourne to Woodford had chilblains so bad that he could not hold his reins. Dido’s green ointment allegedly cured him in two days! He was a bit of a rogue; he collected the leaves of Hawthorn and Blackthorn, and dried and sold them as Tea in Bunhill Row market in London’s East End. He also caught wild birds and sold them. In 1905 he had to leave the forest, along with the gypsy’s and others, and lived in a field in Vicarage Lane. There was much speculation as to his former life; it has been suggested he had been thwarted in love like the Queen from whom he had taken his name. After his death his real name was revealed as William Bell, a London docker and part time fishmonger. From where he had obtained his Herbal skills isn’t known.

The following article appeared in ‘The Teesdale Mercury’ December 4th 1903: ‘In this country of four-square civilisation, silk hats, water arbitrations, and fiscal problems it is quite refreshing to hear of a man who lives in a tent in Hainault Forest and has no money. Dr. Bell, otherwise known as "the hermit of Hainault Forest," appears to be doing no harm to anyone. On the contrary, he keeps the hedges and ditches in order, and performs for the Forest the function that St. Patrick is said to have performed for Ireland: he exterminates snakes. But our civilisation finds no room for such an innocent savage, who asks nothing from it and can pay nothing for its support. Civilisation notices that the Hermit has a couple of dogs. Hermits are not on the schedule of recognised traders; they are not even shepherds or blind men. Therefore they must pay the license. Yet hermits who have stepped out of civilisation do not earn money. It is a horrid “impasse." It is the Hermit contranundum "; Dr. Bell against civilisation with its dog tax. And our sympathy leaks out towards the man who lives in a tent and asks for nothing but permission to live in a tent without being worried.’

The Wilson Family

A descendant of the Wilson family has established that the 1851 census records the Wilson’s living at Wilson’s Cabin (In Hainault Forest). Lambourne Parish register also records baptisms for the family around the middle of the 19th century with the place of residence given ‘as a cabin in the forest.’ Chapman and Andre’s map of 1777 shows a hut to the east of Cabin hill.

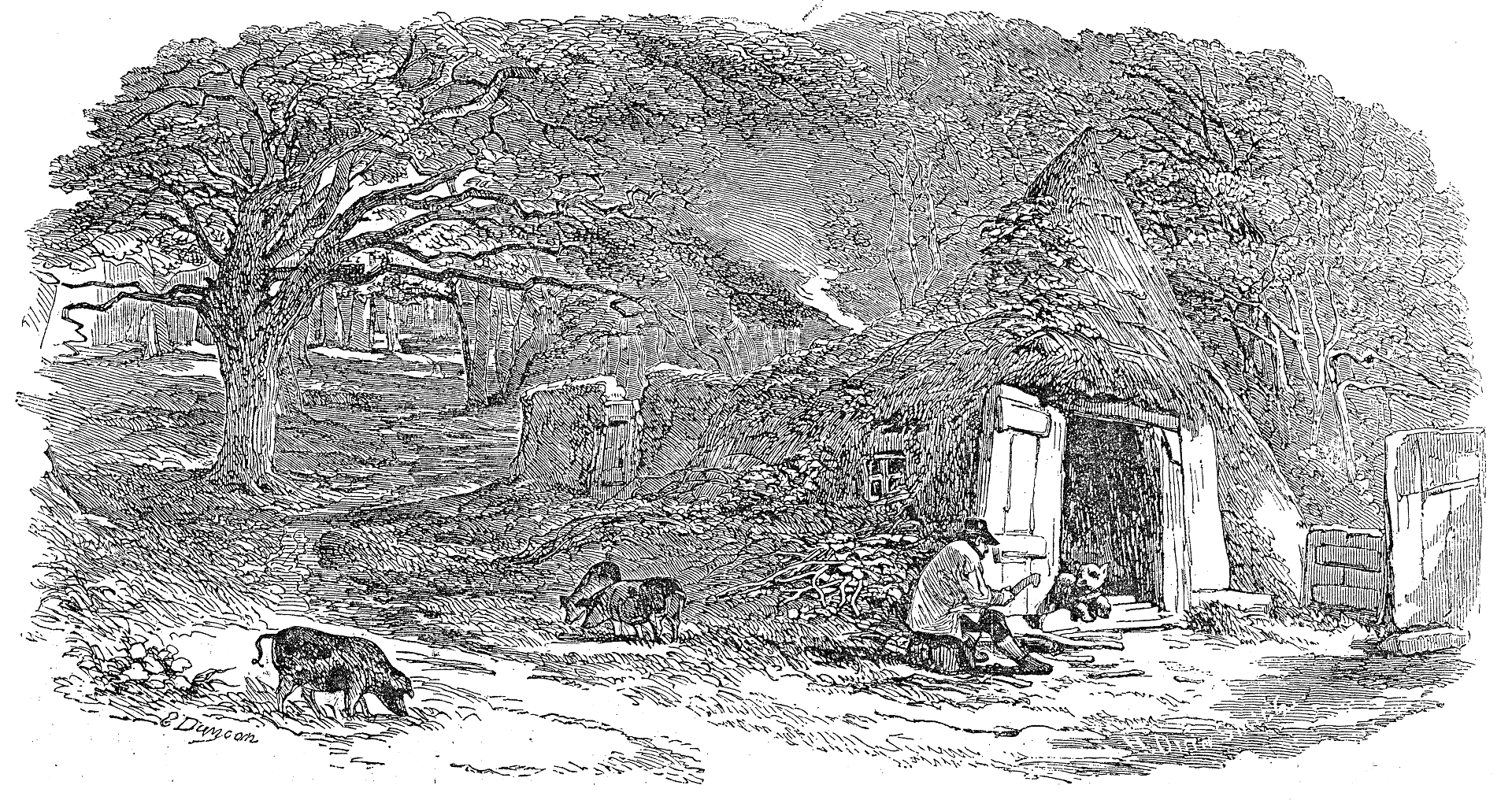

The Illustrated London News of Nov. 22nd 1851 in ‘Sketches in Hainault Forest’ has a wood cut of a ‘Hut in the middle of the Forest.’

The Wilson’s ‘Cabin’ in Hainault Forest. (Near to Cabin Hill.) A woodcut from ‘The Illustrated London News’, Nov. 22nd 1851

Cavill's Walk

A path from the edge of Cabin Plain cuts across the forest towards Featherbed Lane. The walk (Cavills walk) is credited to James Cavill (1802-1888) a wheelwright and resident of "Abridge Cottage" in Abridge. His cottage was opposite the bridge over the river Roding. Apparently he regularly walked along this path.

The Railway Connection

At the beginning of the 20th century an additional railway line was constructed linking Hainault with Woodford, forming a loop with Liverpool Street Station. This newly built 4.5mile railway line was officially opened on 1st May 1903. It linked Hainault, Grange Hill, Chigwell and Roding Valley stations to Woodford station. Fairlop and Hainault stations are the nearest stations to Hainault Forest. The Great Eastern Railway Company ran 20 trains a day initially, but due to its lack of use, the regular service was discontinued on 1st October 1908. In 1927 it became part of the London and North Eastern Railway. (LNER) A regular service wasn’t resumed again until 3rd March 1930.

Work had started before the Second World War on adding this line to the London Underground System by connecting Leytonstone station with Newbury Park station by a tunnel.

At the start of the war in 1939 only part of the tunnelling had been completed; that between Leytonstone and Gants Hill. The Plessey Company’s factory at Ilford was badly damaged during the blitz on East London in September 1940, so production was transferred into the completed section of the tunnel. At its peak over 2000 people worked in the secret factory under Eastern Avenue. During the night raids on London, the local population were allowed to use the tunnel as an air raid shelter.

The tunnel was duly completed after the War and was opened as an extension to the Central Line on 31st May 1948. (No doubt its construction had been started to connect the proposed New London Airport at Fairlop with Central London!) Trains run to Hainault Station via Newbury Park and to Epping Station via Woodford, with driverless automatic trains operating the loop connecting Hainault station with Woodford station.

In 1944 a V1 flying bomb exploded on the West embankment close to the Grange Hill station practically demolishing it. It was rebuilt as it is today; previously it had been a similar design to the Edwardian Station at Chigwell. 1947 saw the last of the steam trains.

Post Second World War

After the end of the Second World War, the plan to establish an airport for London on Fairlop Plain, was resurrected. There were vigorous protests against the site being used as a major airport, and later as a housing estate. The protests were successful, when both schemes had been finally abandoned by 1953. In 1955, Ilford Council purchased the Land for £360,000 from the City of London Corporation. The Corporation had paid a similar sum for it in 1937 as the proposed site for London airport! It would have been barely adequate as the war had rapidly advanced aircraft technology and air travel was increasing rapidly.

Huge quantities of sand and gravel were removed by Ilford Council; in excess of 1,000,000 cubic yards! Rubbish at the rate of up to 300 tons a day was tipped into the empty workings to maintain the soil level. Now most of it is a 360-acre leisure park called Fairlop Waters, with 44 acres of lakes for sailing and angling and includes 18 and 9 holes golf courses and restaurants etc.

With the abolition of the London County Council on 30th June 1963, the Greater London Council (GLC) Parks Department assumed responsibility for Hainault Forest. It then became more like a London Park; with Sports facilities including changing rooms; football and cricket pitches were laid out on the grass areas in front of the farm buildings. A brass band played at weekends and public holidays, and a small zoo was added using some of the buildings and the land behind. The grasslands to the West of the forest, close to Romford Road, were cleared and cultivated to be used as a nursery for growing on ornamental trees for eventual transplanting to various London Parks and streets etc. Most of these were non-native species and some that were left there when the GLC was abolished on 1st April 1986 and have now grown into mature trees.

The Greater London Council in the 1960’s, removed the gorse and broom on the heath-land above the lake, presumably to open up the area, but it was soon invaded by secondary woodland and is now well-established. Gorse can still be seen, struggling for the light, growing among the trees and bushes. A valuable piece of heath-land, rare in Essex, has now been lost forever! Nightingales and Whitethroats used to inhabit this area before it became established woodland. The last Nightingale I heard singing there was in 1991! Other birds were common in the 1950’s. Chiff Chaff, Willow and Garden warblers, Black Caps, Long tailed Tits, Blue and Great tits. Larger Birds like Tawny and Little Owls and Sparrow Hawks, not forgetting the Green and Great Spotted woodpeckers and the Cuckoo; with countless water fowl flying in from time to time including a pair of resident mute swans, the list is endless. Many of these have become locally or even nationally rare and have gone from the forest, never to return.

The largest Badger sett in Essex was at Lambourne End in the 1950’s; in the bank overlooking the golf course. Badgers emerge from their sett’s one hour after sunset; my friend Derek and I quietly waited nearby with our cameras and flash guns at the ready one night, but they must have known we were there, for although we heard them, they didn’t appear. They used to play havoc with the golf greens, digging for worms, so the LCC fenced the course off. The Badgers left the area probably in the 1960’s and have never returned. A second long vacated sett was near the public footpath close to the Bourne Brook, (at the Eastern edge of the Forest.)

In its General Powers Bill for 1966 the Greater London Council proposed a permanent caravan site on the common opposite Angel cottage on Lambourne Road. This raised strong opposition across the whole area of South-West Essex and East London. Charles Pinnell and RJ (Tim) Pratt formed ‘The Friends of Hainault Forest’ and led the fight right up to Parliament. There, the proposal was debated for 3 hours, before being referred to a Parliamentary Select Committee. After the G.L.C had spent 1½ days presenting its case, the committee dismissed the proposal forthwith. They did not even call for the defence from; The Friends of Hainault Forest’ and the Epping Forest District Council.

Some other open areas (plains) that had formerly been kept open by grazing animals within the forest were still being more or less kept open by rabbits, but when mixamatosis devastated their population in the early 1960’s, secondary woodland quickly invaded, now most of these ‘plains; have become part of the woodland.

Ownership of Hainault Forest from 1903

London County Council, 1903 to 30th June 1963

Greater London Council, 1st July 1963 to 31st March 1986

Split into 3 along local authority boundaries, 1st April 1986

Woodland Trust takes over the Essex portion on a 50 year lease, April 1998

On the 1st April 1986, when the G.L.C was abolished, the forest was divided according to existing local authority boundaries, dissecting the forest into three parts. The London Borough of Redbridge had the largest portion; Essex County Council the ancient woodland to the North and The London Borough of Havering a small area in the South eastern corner. It was agreed Essex C.C. and L.B of Havering would pay L.B of Redbridge to administer all three areas. (The Redbridge and Havering portion was the woodland that was previously owned by the Crown.)

This arrangement continued until April 1998 when Essex County Council withdrew from the arrangement and leased their area of the forest, 129.1 ha (319acres), to the Woodland Trust on a 50-year lease with an annual grant to manage it. This included 244acres out of a total of 256 acres of the ancient woodland left in Hainault.

Between the wars, cattle and sheep were grazed on the grassy areas at Foxborough’s farm and the farm buildings were used as tea rooms. At the start of the Second World War, much of the grassland was ploughed for growing food and a series of trenches cut across the flat areas around Foxburrows Farm running North/South to prevent any enemy aircraft from possibly using it as a landing ground. A Land-mine parachuted down and landed in one of the trenches, local children investigated and climbed all over it, trying to remove pieces for souvenirs! The bomb disposal squad arrived and promptly detonated it. The resultant crater was said to be big enough to hold three buses!

Sporting activities, football, cricket pitches and cross-country running, were encouraged when the LCC and GLC were in control. The changing rooms were built close to the site of the Foxburrows Farm buildings. One of the Farm buildings was used as Tea Rooms between the wars and immediately after the Second World War. Animals were housed in some of the old farm buildings during the time the LCC were there, and the practice continued under the GLC. Both authorities had a zoo licence, allowing some exotic species to be there, including peacocks. When Redbridge (who did not have a zoo license) took over the administration, some animals had to go. Today there are some rare breeds of sheep, pigs, chickens, rabbits, cattle and donkeys to be seen - they are much appreciated by the younger visitors.

The 1976 Drought

The bed of the dried up lake in 1976

The driest year ever recorded was 1976. It began in May 1975 with that summer being the hottest for 28 years resulting in water shortages. The following winter rainfall was well below average and by April 1976 the drought situation had become serious. The heat wave continued right through the summer, temperatures did not fall below 27C from 22nd June to 16th July. The grassland was parched, turning brown then white; the trees in the forest suffered greatly, causing premature leaf fall. The Birch trees, Betula pendula, suffered particularly badly, with leaf fall by mid summer; many of the younger trees succumbed entirely. The water level in the lake fell dramatically, with the northern and eastern areas drying up completely, becoming hard and cracked. It then became possible to walk to the tree and ivy-covered island, perhaps for the first time since it was dug, nearly 70 years earlier! (WWII bombs may have caused the three, 3m diameter concave depressions I noticed were on the island!)

The GLC took the opportunity to deepen the dried up areas of the Lake by bull-dozing the drying silt and creating firmer banks, shoring them up with Willow stakes, most of which rooted and have since grown into mature trees. The Lake did not dry up completely; there was still some water in the deeper part to the West of the island. This was dredged deeper by pumping the silt and water on to the higher ground to the North East of the lake and into the higher of two artificially constructed lagoons, one draining in to the other, thus allowing the sediment to settle with the ‘cleaned’ water draining back into the lake. Large flat shells of the fresh water swan mussel,

Anodonta cygnaea, along with shells and bullets etc. from WW1 were dredged up among the debris that was deposited in these lagoons.

The trees growing along the Northern edge of the Lake grew from the Willow stakes that were driven in to shore up the bank after it was dredged in 1976.

The Big Blow

The great storm of 1987 was a violent extra tropical cyclone that occurred on the night of October 12th-13th 1987. It was the greatest gale for centuries causing havoc across the Southern half of Britain. With the highest gusts recorded at 120 mph, much damage was done with many trees blown down, causing many roads and rail lines to be closed. In Hainault Forest the gales blew down many trees, particularly the old Hornbeam pollards. Many hundreds lost limbs or suffered other damage.

With over 800 trees damaged or blown down, the forest was a sorry sight! Again in January 1990 more gales wreaked further havoc, this time the Birch trees suffered the most, but fortunately it was much less than the carnage that had been wrought in the 1987 gale.

Hainault Lodge, a Local Nature Reserve

The 14 acre (5.5 hectares) site at Hog Hill, where Hainault Lodge had been until it was demolished in 1973, became completely overgrown; so in 1986 the site was acquired by the London Borough of Redbridge and was added to the Hainault Forest Country Park as a nature reserve on 5th September 1995. It was officially opened by the Mayor of Redbridge, Councillor Ronnie Barden, on 15th December 1995. Volunteers have since worked hard removing the invasive Sycamore trees and scrub; paths have been put in and it has been made as natural as possible.

Hainault Lodge was built in 1851 at the time of the disafforestation of Hainault Forest. It replaced a much earlier Hunting Lodge. Its occupants were varied and included Frederick Green JP, one time High Sheriff of Essex, who rebuilt the Lodge in the 1880's. He was the last person to live at Hainault Lodge and is buried at All Saints Church, Chigwell Row. It was rumoured that he had refused to give the North Eastern Railway Company permission to cross his land unless they gave him his own station – i.e. Fairlop. Could this be the reason why the three stations, Barkingside, Fairlop and Hainault are rather close together? At that time there was very little housing or development around Fairlop!

During the Second World War the lodge housed the Officers from RAF Fairlop. After the war it became an annex to Romford’s Oldchurch Hospital for a few years, but by 1966 it was no longer in use. It had lain empty for another 7 years before it was finally demolished in 1973.

The 100th Anniversary of the Dedication of Hainault Forest

On 15th July 2006, the Centenary celebration on the opening of Hainault Forest took place on the fields in front of the Farm buildings at Fox-burrows Farm. John Buxton, a grandson of Henry North Buxton, (Brother of Edward North Buxton?) Lord Carrington the great nephew of Earl Carrington and her Majesties Lord Lieutenant of Essex Lord Petre, were among those attending the celebrations. After the speeches the audience were entertained by the Redbridge Music School. Many local clubs contributed exhibits and with many side shows it was a great occasion.

The centenary was a double celebration as the Woodland Trust, who administers the Northern part of the forest, has purchased an adjacent 134 acres of farmland, buffering and extending the ancient woodland of Hainault Forest, together with other land owned by Essex County Council.

100 years ago on 21st July 1906, the Right Honourable the Earl Carrington, G.C.M.G., President of the Board of Agriculture and Fisheries made the speech of Dedication to a distinguished company from the London County Council and many local authorities on Cabin Hill in Hainault Forest.

The website thanks Peter for sharing his history of Hainault Forest.